Cultural appropriation

[Warning: this is me in ranty, pissed-off mood. I apologise for picking targets and basically offloading my anger on them, but I honestly feel I can’t make you understand what I mean without pointing at specific bits. Many thanks to Rochita Loenen-Ruiz for reading this before it went live]

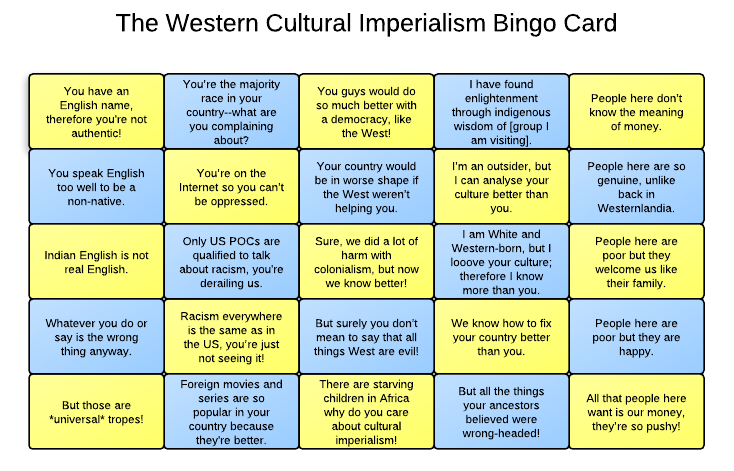

Apropos of nothing and just for the record: when people complain about cultural appropriation, they’re not all [1] saying that outsiders shouldn’t write cultures foreign to them. However, what I suspect they’re saying [2] is this: some outsiders (rather more than you think) will get cultures egregiously and disrespectfully *wrong*. That, even if a lot of (other outsider) people think that a certain book/story did a great job of introducing them to a fancy new culture, it doesn’t change the orientalist/racist clichés or simply the bad facts that are presented in said fiction.

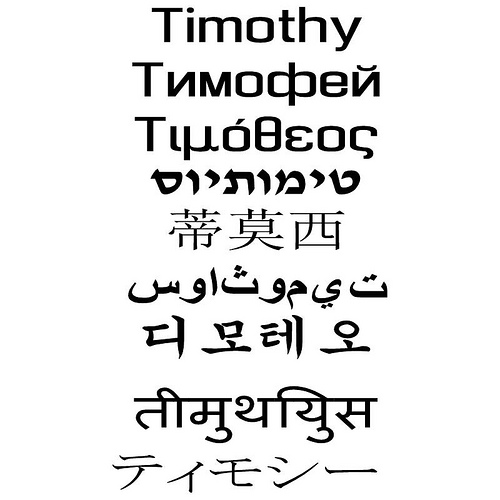

And when I say bad facts I don’t mean niggly details that would require weeks of research: I mean really, really bad facts akin to calling everyone in a French novel “Dracula” because everyone knows Dracula is a typically French name. Facts that should have been a part of any basic research process, and that make the reader doubt the author really cared about the culture they were so “thoughtfully” depicting. Names. Food. Religion. That kind of thing.

You’ll think that this is a tiny minority; a 0.01% of writers who get things wrong and are rightly excoriated for it. Thing is… this happens WAY more often than you’d think. This is NOT a tiny minority. I’m not saying it’s a 99.99% of fiction either, but cultural appropriation is not a negligible or insubstantial phenomenon. A significant amount of fiction out there makes me doubt much thoughtful research (or much research at all!) was involved.

To take just one example: the last few stories set in China I have read [3]. One of them, set in historical China, mangled the historical timeline so badly I wasn’t even sure it was the real China, and inexplicably forgot to have any kind of ancestor worship, which is a bit like doing medieval France without Christianity. One of them, set in a futuristic China, used the timeworn tropes of Chinese being horrible to their own women (because, you know, Confucianism [4]) and had said women rescued by Westerners (because quite obviously those poor Asians can’t rescue themselves). And the last one, set in what purported to be Ancient China, had a concerted state-supported effort aimed at imprisoning, mistreating and killing dragons (we’ve been over this before, but Chinese/Vietnamese dragons are NOT evil, they’re Heavenly beings. This is a bit like having a historical medieval Europe where kings authorise the chasing and killing of angels. Possible, but a. you’re not going to get very far because angels are way more powerful than humans b. you’re not going to stave off the wrath of God for very long [5]) For bonus points, that story also had an evil character on a quest for immortality that he later renounced because he wanted redemption. Er. No. Quests for immortality are perfectly fine in Chinese thought (see Daoist immortals. That’s perfectly OK, and in fact deeply respected).

Again, I’m not Chinese. But Vietnamese culture has a heck of a lot of overlap with Chinese culture, and none of these feel remotely OK to me. In fact, they feel like Western thought grafted on top of what someone thought were the “cool bits” of Chinese culture. And, without exception, all of these had glowing reviews by people convinced that those were accurate and nice representations of Chinese culture. Newsflash: no, no, and no. When a writer is perpetuating horrible clichés in the course of their writing, when they’re propagating transparently false ideas of what it means to live in a place and/or a time period… This is cultural appropriation, and it’s bad–and whether said writer meant it or not doesn’t change the fact that they’ve egregiously mangled someone’s culture through lack of care. It’s the bit that makes a lot of people angry, and quite justifiably so. [6] It’s not the fact that writers take cultures that aren’t from their traditions that attract people’s ire; it’s the fact that the depiction of those cultures are badly inaccurate on mind-boggling levels.

(there’s an easy way to avoid this if you’re using a 21st-Century culture btw–grab someone from said culture and ask their opinion about the basic stuff in your story)

Anyway, that was my afternoon rant. Apologies again, and thanks for listening. If anybody wants to weigh on how they feel about the subject, I welcome thoughts and discussions!

(also, if any Chinese people are reading this and feel that any of the examples I used aren’t appropriate, I’d be quite happy to be corrected. I would have used Vietnamese culture, which is the one I’m most familiar with, but Vietnam hasn’t been the subject of quite so many books and stories and I didn’t really have enough examples for this…)

[1] Some of them are, and I understand and respect that feeling. Likely, the reason they don’t want outsiders writing about their culture is exactly what I’m going to outline in this post–too many people have been doing it badly, badly wrong.

[2] Again, not claiming to walk in people’s heads. Seen the feeling a lot on the internet though.

[3] I’m not Chinese, as is by now evident; and China itself is huge and multifaceted. However, Vietnamese and Chinese cultures have a lot of points of intersection, especially when we’re talking Ancient China and Ancient Vietnam, since the second was basically a colony of the first. And also, I can spot an Orientalist cliché when I see one.

[4] Not saying Confucianism didn’t do a lot of damage; however, you have to realise that you can’t base a description of modern China/Vietnam on mores that have gone out of fashion or been severely toned down in the 20th Century. Having China follow old-school Confucianism, again, is a bit like having Europe still follow the hard-core Christian mores of the Middle Ages. Er, no?

[5] ETA 2016: having actually written that story *cough*, I’m going to amend that into “you totally can, but be aware what kind of vibe it ends up giving the final product” (in this particular case, it’s possible, but very very hard not to shade into horror).

[6] I very probably committed bad mistakes in the Obsidian and Blood books (well, not “very probably”, I know at least two errors that I wish I could fix), though I did my best research-wise. I do hope none of them are on that egregious level of failure, but if they are, I apologise profusely. I was much less aware of that kind of issues when I wrote Servant, and it shows.

The above is something that I’ve often heard quoted when speaking of “writing the Other” [1]. And I’ve been struggling with it ever since I heard it; because it rings fishy to me. And yet there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with it; and indeed, much that is right. Of course we’re all human beings. We’re born and we live and we age and we die. We love and we care and we hate and we fear. We have parents and grandparents and some sort of family; and a non-insignificant bunch of us will have friends and children and partners. There’s a whole spectrum of experiences and emotions that we share on what, for want of a better word, I think of as the human continuum. And, given that a few centuries ago people of a different colour or gender or creed were thought of as no better than beasts, I’m certainly not going to complain at the impulse to declare us all part of the same species.

The above is something that I’ve often heard quoted when speaking of “writing the Other” [1]. And I’ve been struggling with it ever since I heard it; because it rings fishy to me. And yet there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with it; and indeed, much that is right. Of course we’re all human beings. We’re born and we live and we age and we die. We love and we care and we hate and we fear. We have parents and grandparents and some sort of family; and a non-insignificant bunch of us will have friends and children and partners. There’s a whole spectrum of experiences and emotions that we share on what, for want of a better word, I think of as the human continuum. And, given that a few centuries ago people of a different colour or gender or creed were thought of as no better than beasts, I’m certainly not going to complain at the impulse to declare us all part of the same species.