And now for something completely different: a few weeks ago, I complained on twitter that the science in SF seemed oddly stuck in the 19th Century, both the actual science research (which seemed composed mainly of individual mad geniuses in their garages having huge conceptual breakthroughs), but also its close siblings, the engineering projects that make up so much of SF (like building space stations, space launchers, etc.), and which seem to bear little relation to anything resembling real life.

I’ve complained about science here, but now for bonus points: engineering projects!

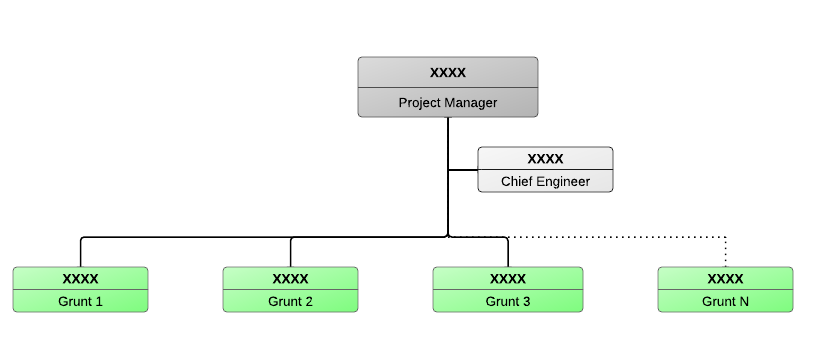

So, exhibit A. This is how a large-scale project looks according to most SF stories I’ve read:

.

.

Basically, a project manager who is God, or as near to God as matters, with anything from a hundred to thousands of (mostly) nameless, faceless grunts under him doing all the work. The story then tends to be either from the point of view of the project manager as he attempts to solve a pressing technical problem, or, less often, from the point of view of a harried grunt who has to solve a problem before the all-powerful project manager descends on them like the wrath of God (I’ve been nice here and thrown in an Assistant Project Manager, who will provide the necessary dialogue for as-you-know-Bob scientific exposition or provide a sympathetic ear to our grunt’s troubles).

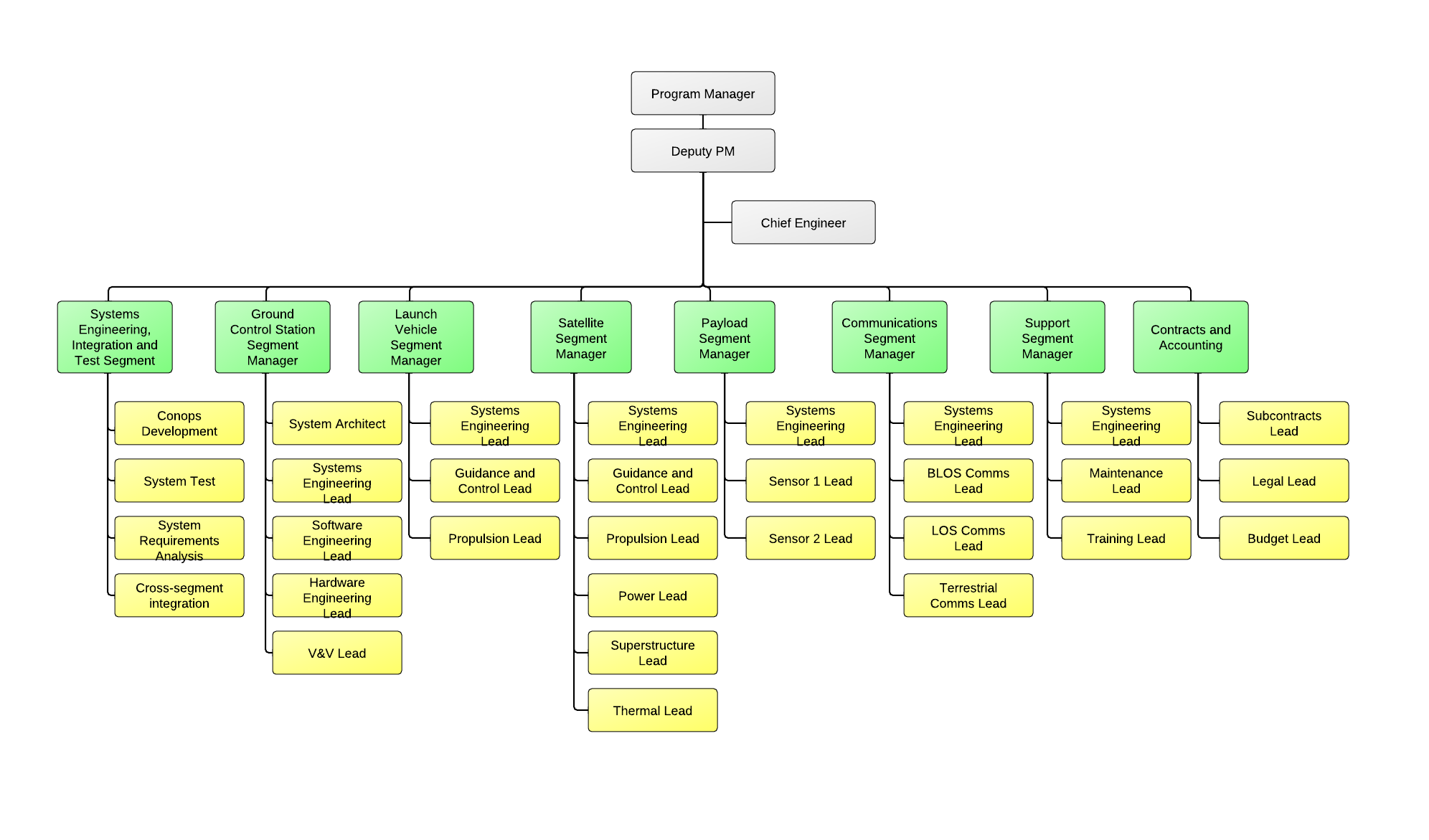

Exhibit B: by contrast, this is what a real large-scale engineering project looks like in the 21st Century [1] (click to zoom):

Yes, it’s rather more complicated. There’s also two significant differences worth noting: one, the bottom boxes of the chart are not people, but team leaders, ie every bottom box still unfolds into your actual grunts. Second, I’ve cut at the level of the project manager to keep both graphs at the same scale, but there’s a significant extra layer at the top, which includes our project manager’s immediate hiearchy (his boss), a committee of peers (who follow the project and determine whether to continue funding it or not according to various Go/No Go criteria), and one or several sponsors (who champion the project within the company and to whom the project manager is accountable). Let’s not forget interlocutors outside of the company as well: the actual customer (ie the person paying for the delivery of the project; for instance, in the case of missile systems, the army is paying; in the case of a space station, you can imagine a conglomerate or a government paying…); subcontractors who have to be monitored, other companies working on related segments of the project (for instance, on a space station project, one company does the infrastructure, one company the climate control…).

So, yes, you’ll notice the same thing as with scientists: no project manager exists in a vacuum. They’re always accountable to someone for something (and when I say “accountable”, I mean all important decisions made are scrutinised, not that they’ll be judged solely on whether the project finishes appropriately. Will come back to “appropriately” in a minute).

Another thing is that responsibility is shared and diluted: note that the second org scheme has divided the satellite into different subsystems like the ground portion, the comms system, etc., and assigned different responsibilities within those subsystems. There is no grunt vs project manager system, but a carefully organised hierarchy of decreasing responsibilities fanning out from the system level, which ensures that everyone knows what they’re doing, and most localised problems do NOT make it back to the project manager, who has way more important things to do than concern himself with every little problem. On that same subject, a project manager is very seldom in the field, and most of their day is spent in meetings and in discussions with people (I always feel like laughing when a project manager on a space station spends their time touring the construction site and offering advice on stuff that most workers would take care of on their own…)

Finally, one thing that bugs me in engineering projects in SF is the lack of tradeoffs. Science tends to be “all shiny”, ie when a problem is posed, there is very often a perfect solution, one that meets all the needs and provides all that is expected. In real life, science is *never* shiny, and is almost always about compromises: things can be infeasible simply for technical reasons (for instance, no radio comms will provide the necessary reliability over the necessary distance), they can be infeasible for cost reasons (radio comms can be provided, but not within the allocated budget), and they can be infeasible because of time reasons (radio comms can be provided, however they will take eighteen months to be developed and tested, and we only have twelve months to deliver the system). In my line of work, we call that a QCD triangle (quality, cost, delivery): you simply can’t have all three items at the same time!

Now, coming back to that “appropriately”: a project is of course judged on whether it finishes on time, with the appropriate features and within budget (incidentally, a lot of SF projects never really seem to worry about either delays or costs…). However… you don’t wait until the project is finished to judge this! In addition to regular progress reports, there’ll be regular “milestones” which correspond to important decisions and/or steps in the project’s life. At those points, the project will come under scrutiny more intensely (by the peers, the hierarchy etc.), and will have to provide quite a few elements of justification for said decisions (and the project manager might well be part of a collegial decision process in those stages).

So, there you go, a short Engineering Projects 101–I’ve had quite a few years working on those by now (though admittedly mainly in a European work culture), and quite a few years reading SF, and so far I’ve been very disappointed by the portrayal of these. I might, of course, be picking up the wrong books/short stories/movies… Have I forgotten any gripes people have with engineering in SF? Are there any pieces that do a decent job of getting to grips with this kind of complexity? Feel free to argue/discuss/disagree in comments!

[1] Fake example for a satellite launcher. I copied it from a blog–not saying it’s a typical org, but it’s most certainly one that could exist and apply to a bona fide project.