Article: The Rule of Names

(yes, I like Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea. Sue me)

I was planning to do a longer and more detailed post, but time, once again, has got away from me (sigh, already so late on so many things. Clearly, I need a better juggling teacher). So here’s the shortened version…

There are few things that throw people out of your carefully researched novels faster than getting names wrong. I once opened a novel that had a French protagonist, and didn’t get past the first page because all the French names looked like they’d been fished out out of an internet baby list [1]. Names are one of the first contacts people have with your characters, but they’re a surprisingly common source of fail in fiction.

There are few things that throw people out of your carefully researched novels faster than getting names wrong. I once opened a novel that had a French protagonist, and didn’t get past the first page because all the French names looked like they’d been fished out out of an internet baby list [1]. Names are one of the first contacts people have with your characters, but they’re a surprisingly common source of fail in fiction.

The main reason they’re a source of fail is because often, people assume that the same naming rules they’re familiar with will apply everywhere in the world. And that’s hardly the case, as countries and cultures can have vastly differing naming customs. For instance, we don’t have middle names in France and think it a very odd concept when it does crop up in American movies (and Vietnamese do have an intercalary name, but it doesn’t have the same function or characteristics as a US middle name).

Here are a handful of examples to demonstrate the common traps into which writers can fall: they shouldn’t be taken as actual knowledge, more like an indicative checklist that things that can vary across cultures. Also, not an exhaustive list, as I drew from those cultures I was at least vaguely familiar with, which were mostly Vietnam, France, and Russia–but already, you can see that names can follow very different customs!

Some errors I’ve seen in books (beyond the obvious ones of picking names that are ridiculous or don’t exist):

-Getting name order wrong (Chinese/Vietnamese last names come before the intercalary name and the first name: for instance, someone whose last name is Nguyen, intercalary name is Thi and first name is Hanh would be Nguyen Thi Hanh, not Hanh Thi Nguyen)

-Not understanding that you might have little choice for last names. In Vietnam, 99% of the population bears a total of 14 last names, which means you just can’t invent a Vietnamese last name if you feel like it! However, first names aren’t taken from an accepted list but rather chosen by the parents on the basis of words/concepts they like (there are rules/guidelines/usages, but I won’t go into them here), which means you can have extremely uncommon first names. A related one is Russia, where people have a patronymic name (derived from their father’s first name) and a family name–which means names have a very distinct structure.

-Not understanding what marriage does to last names (in a lot of cultures, women don’t actually change their name to match their husband’s)

-Getting diminutives wrong (a lot of cultures have different patterns than the usual Anglo one of shortening someone’s name by a few syllables to be more informal or more affectionate. See, for instance, Russian. Getting affectionate in Vietnamese mostly involves pronouns rather than diminutive forms of the names–OK, partially because Vietnamese first names are so short!)

-Conversely, not understanding how to address people formally. Using someone’s last name isn’t always the formal method to address them. In Vietnam, you use Mr./Mrs [2] + First Name to address someone formally.

I’m sure there are plenty more things to watch out for, but I’m only familiar with a handful of cultures… Anyone else have tidbits about how naming principles differ across cultures?

[1] Internet baby lists can be very dangerous, as they’re the first things that pop up when you’re looking for “names from xxx culture”, but are either badly compiled, or list all possible names without warning you if they’re popular or dorky choices (hint, for instance, don’t try calling your French female MC “Cunégonde” unless you want everyone laughing at her).

[2] “Mrs.” actually covers lots of different modes of address depending on how old the speaker is compared to you (“Grandmother”, “Aunt”, “Elder Sister”, “Younger Sister”, “Child”…), but this is very complicated and beyond the scope of this list!

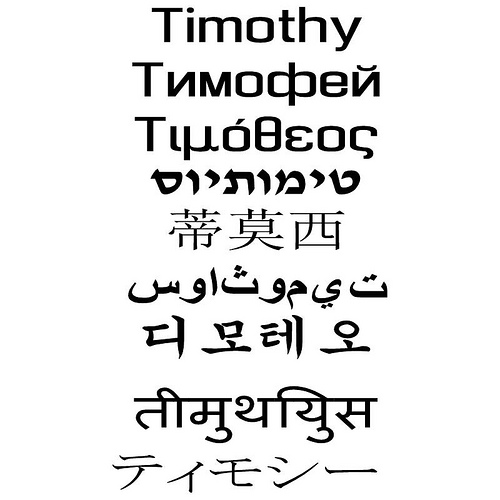

(picture credits: Timitrius on flickr, shared under a creative commons attribution share alike generic license)

0 comments

Ferrett Steinmetz

I’m writing a Korean protagonist now, and was shocked at how much research I had to do on what her name was. I spent probably an hour doing Wikipedia reading, just trying to find a reasonable-sounding name and understanding which part was which.

And even then, I’ll probably still get it wrong. Bleah. But I’m trying.

Brian Dolton

I know you mentioned the problem with your readership not understanding that “sister”, as a term of address in some cultures, does not imply an actual blood relationship; I’ve had the same problem with the use of “grandmother” as an honorific. As a result I’ve tended to drop such things out of short stories, and am reserving them for novels where there’s room to explain or clarify how these things work a bit better.

Names, yes, names are difficult. The short-cuts I’ve tended to use are not lists of baby names, but looking up national sports teams. Obviously in some countries, nationality itself has become somewhat complex (look at the ethnic/racial make-up of many Western European soccer teams, for example…) but it can be a handy starting point for identifying naming patterns, which names are very common, how names vary between men and women, etc. I think I was first struck by this many years ago (1994 World Cup?) when commentators noted something like “every player who’s ever represented Bulgaria has had a surname ending in “v” ” – because Bulgarian surnames (as in many East European/Slavic countries) are still hugely patronymic, and “-ev” is the male partonymic ending.

I still haven’t fully got to grips with Spanish (and to an extent Mexican, and likewise Portugese/Brazilian) naming conventions, which involve multiple forenames and multiple family names.

ANd then there’s clan names/relationships – the Dine (Navajo) have a clan system with all manner of subtleties I wot not of. If I ever need to use them in a story then I shall have to do some major research.

And that’s what it comes down to. Research, research, research. It’s a great excuse for never actually writing anything…

Andrea Harris

Naming conventions have always been interesting to me. Even in Western Anglo culture they differ — for example, I have a middle name but it’s just because it’s customary in my family but there’s nothing religious about it; Catholic kids sometimes have a middle name and a saint’s name; Jewish kids (I think, and I don’t know if this holds true across Reform/Conservative/Orthodox) can’t be named after a relative who is still alive (so there are no “William Goldstein Jr’s”), and so on.

Mistakes white Anglo writers make are really irritating because none of this is a secret, all you have to do is a little research. Like, calling you Russian woman character “Irina Somethingkov” — when the ending should have been “kova” for a woman. Also not giving her a patronymic, not understanding when you should call someone first-name/patronymic and when you should call them by their nickname… And so on.

prezzey

I’m Hungarian and I’m not even sure what the “right” Hungarian name order would be in an English-language SF work.

The Hungarian native order is last name first, then the first names. No patronymic. (Some people might have a Slavic patronymic as their surnames, but these are static and fixed, do not try to infer the name of the father from them.)

But when Hungarians write something in English, it’s very common to reverse the order to avoid confusing non-Hungarian-speakers. Paradoxically, this often confuses them more!

For example, I go by Bogi Takács and Bogi is actually my first name (actually a diminutive form of my first name that is easy to spell, but people call me Bogi in real life too… well, they often call me prezzey in real life too! 😀 ). Since Hungarian first names and last names are very distinctive and you can usually tell which is which if you are Hungarian (there are only a handful of exceptions, mostly first names which can also be last names, not the other way round), it’s not much of an issue for Hungarians. But when foreigners try to guess which is the first name and which is the last, it usually results in a LOT of confusion.

Also, if you name a Hungarian character Béla, or have Kovács as their last name, expect to be laughed at. These are cliché names often used for comedic effect, or as placeholders… though there are real people with these names and both are quite common. (Takács is also an extremely common last name, but not used for comedic effect…)

And diacritics are not to be assigned at random. I used to think that was self-evidential, but I came across a story on tor.com (so not a small venue!) where the author wasn’t aware of this…

Keith West

This is a very informative post, as are the comments. I was aware of Russian naming conventions, although I don’t think I completely understand all the details yet. The Vietnamese naming conventions were completely unknown to me, as was the fact that the French don’t have middle names. This was a good reminder to do my research because I’m planning a historical fantasy with Spanish characters. Thank you.

aliette

@Ferrett: very different naming customs from the US ones, to be sure! Can’t you find a Korean/Korean-American to help you out? I’m sure they must be able to tell you if a name is screwy or not…

@Brian: I’ve heard the sports team thing and it makes excellent sense, thanks for sharing! (though I’d be a little worried because I’m not quite sure it reflects societal makeup–for instance, French teams seldom include members of the upper to upper middle class, so picking names for people like these from soccer teams would be problematic…) I have basic Spanish knowledge, but it’s just good enough not to be laughed out of Spain 🙂

@Andrea: yup, it’s also very different across different communities and religions! And yes, I’m pointing out very basic mistakes here–as you say, it’s not a secret and only requires a little digging (I’m willing to cut a lot more leeway on people getting the “class” of French names wrong, because it’s harder to tell which names are likely to be upper class vs working class).

@prezzey: awesome, thank you very much! (and hahaha, random diacritics. Moments like these, I laugh because it’s either that or crying).

@Keith: thank you! French can have “baptism names”, ie extra names that are given after a baptism, but they get tacked on as part of your first name. For instance, someone’s first name would be Luc, and their baptism names would be “Marie Stéphane Henri”, but on their ID they would just have: “first names: “Luc Marie Stéphane Henri” “, and they’d likely go by Luc (not always the case. Sometimes people will fish a name from their baptism name and go by this).

Cora

I always cringe whenever I see twentysomething German characters in books by Anglo-American authors given names that went out of fashion around 1960. It’s not that there aren’t young people with old-fashioned names, but there’s usually a reason for it, e.g. they were named after a grandparent or come from a conservative family.

I can often tell by a German person’s name how old they are, what part of the country they are from (East and West Germany had very different naming practices and South and North vary as well), what class they are from, whether they have an immigrant background, etc… Particularly the class connotations of certain names are very strong and people with names that are considered “underclass” often face discrimination at school and in the workplace. And foreign authors mostly get it wrong, e.g. a modern teenager is more likely to be named Kevin than Kurt.

Brian, I’ve used football and other sports teams as sources for names as well. Though a potential pitfall is that a lot of athletes come from immigrant families. For example, Germany has Olympic medalists named Dimitri and Oksana this year, neither of which are common outside immigrant communities.

As for getting names wrong, my all time favourite example involved an aristocratic gentleman named Otto Graf Lambsdorff, who was West Germany’s secretary of the economy in the 1980s. Otto is the first name, Lambsdorff the family name and Graf is the title, equivalent to Count. Otto Graf Lambsdorff visited Singapore on official business and of course the local newspaper had a report about the visit. Now Singaporeans are used to West European naming conventions and normally get them right. But the fact that this politician had three names, one of which was an aristocratic title, must have confused some poor journalist so much he or she wrote the headline “Otto visits Singapore”. Which amused any German expat who chanced to read it, because Otto (last name Waalkes, but he usually only goes by his first name) is the name of a very popular German comedian.

Rosario

In Spanish, it’s [Given Name(s)] [Father’s 1st surname] [Mother’s 1st surname].

So if my dad’s Juan Pérez García and my mum’s Teresa González Rodríguez, my legal name would be Rosario Pérez González. I might choose to use that, or just to use Rosario Pérez (especially for informal purposes). Both usages are common.

That one’s pretty well known, I think, but people often get it wrong, like football commentators calling football players by what’s actually their second surname. And you know what, I completely sympathise. It’s kind of natural to assume that the naming convention you’re used to is universal. I was embarrassingly old before I realised that it wasn’t that English speakers didn’t use their second surname, they didn’t actually have one!

A couple more tidbits, that are less well-known:

If a woman has more than one given name, and the first one is María, it’s very probable she will normally use her second name. That’s because so many women are given that first name (originally to honour the Virgin Mary, but often just for tradition’s sake), that it’s a bit impractical to have so many Marías around. In fact, it’s very common to have sisters who are both María (I’m María del Rosario, my sister’s María Lucía, and we just use Rosario and Lucía).

Married names is another one you’ll want to think carefully about, because it will say quite a lot about a character. Spanish doesn’t have the concept of a maiden name, because women don’t change their name upon marrying. What they can do is attach their husband’s first surname to their two surnames, preceded by the preposition “de” (meaning “of”). So in the example above, my mum could use Teresa González Rodríguez de Pérez. This isn’t a legal name at all, you just choose to use it. And whether you do or not, can tell you a lot about how traditional-minded the person is. I can’t talk about the whole Spanish-speaking world, but where I’m from, young people use it less and less, as it’s considered old-fashioned (you’re basically saying you belong to your husband, which many of us find just horribly offensive).

Aliette de Bodard

@Cora: yup, that’s exactly what I was saying to Brian, sports can be a very biased sample because of so many immigrants! And class, origin and generation definitely play a very large part in which names are given to whom (and lol on the Singaporeans. Wonder if that didn’t have to do with language though? In Vietnam if you want to refer to someone you use their first name, so if François Hollande came to Vietnam he’d be Mr. François rather than Mr. Hollande…).

@Rosario: aw thank you, that’s awesome information! Didn’t know that about the “de + husband’s name”, I can see why that would become offensive quite quickly…

French, strictly speaking, has no maiden names: the name I was born with is the name the French state will know me under until I die. The state does grant you permission to use your husband’s name (as your own, or as part of a compound) as a courtesy, but that’s not your “legal, official” name.

Farah

One more for you:

Immigrants in the UK tend to choose English sounding names for their kids; their kids then name their children something exotic and often of no nearby culture at all; then in the last generation they go all traditional.

I have no idea why this is the case, but I have observed it in my own community and in the communities in which I teach.

Next Friday

I had to remove little-details LJ community from the default view because it was getting ridiculous. “Oh, tell me what endearment or nickname would one use for such and such name!” with no indication of who the character was and who would be using the endearment.

Everything matters.

Age, age difference, gender difference, social status, marital status, time, location, ethnicity, RELATIONSHIP, the presence of other people around, formal/informal setting, etc, etc.

But as far as Russian conventions regarding names go, there are quite a few that are important.

– Most last names are gendered. Some are not.

– First names generally have formal version and informal. Informal names are used by friends and family. Formal name is written in your passport and used along with a patronymic. Sometimes they are the same. Sometimes there can be many informal versions (and forms) of the same name. Most of the time the connection between formal and informal names is fixed. In other cases it can be flexible.

– Everyone has a patronymic. People actually usе them in formal situations. Some people can be addressed casually by a patronymic only, others can’t.

– Patronymics are not used with informal names.

– Additional forms of address are not used with name-patronymic combination. (I won’t even go into how they are used.)

– A lot of last names were derived from patronymics. One can tell which is which by their forms. Yes, it is possible for a last name to have the same form as patronymic, but in vast majority of cases they are different.

– There’s no concept of middle name.

– You might or might not be able to tell someone’s ethnicity by their name.

– Most women change their last names when they get married. Some choose not to.

Swimming in this water without help is impossible. If someone doesn’t realize that, they probably shouldn’t be writing a book with Russian characters in the first place, because inability to estimate the complexity of a project before it starts will contribute to the project’s failure in general. Of course, some writers think that insufficient research is no biggie. It’s ok. We won’t be remembering their names either.

Aliette de Bodard

@Farah: thank you! And yes, I’ve seen the first step of this in France (Vietnamese-French kids are named with very traditional, often old-fashioned French first names. I’m assuming it’s done not to stand out in a crowd? Very often the first thing parents are worried about…)

@Next Friday: thank you so much for posting those! (I confess to laughing quite a bit at little_details, because when they ask questions about French or Vietnamese cultures they tend to forget half the necessary information!) I’m not familiar with Russian naming customs other than very distantly (my husband took 11 years of Russian and we have Russian friends, but obviously we never go into the details of how to call people in Russia 🙂 ). But yes, if you’re an author and writing a story set there, it behooves you to get the basic stuff right. Or to run it by someone who helps you.

Karen Williams

Along with Farah’s comment, one of my friends in LA pointed out that there’s a large section with Russian immigrants, who wanted their kids to fit in, so they named the kids with common American names. But Los Angeles has many residents of Mexican ethnicity, so there were a lot of names like Diego Gagarin and Jose Yeltsin in LA.

Next Friday

Karen, do you mean that Russian immigrants would use Jose and Diego? That’s definitely not the case in the East Coast. Here the trend is that they choose common names that have a Russian equivalent, so that they could continue using the corresponding informal name in the family.

Cora

Aliette, I suspect that the “Otto” goof was due to the Singaporean journalist knowing that the secretary had an aristocratic title and accidentally thinking “Otto” was the title. It’s an easy mistake to make, considering there have been several German emperors, dukes, electoral princes, etc… all called Otto.

Farah, that’s interesting about the naming practices of UK immigrants. Here in Germany, Turkish immigrants have largely stuck to Turkish names for two generations now. Only within the last ten to fifteen years have Turkish Germans started giving their children non-Turkish names. For example, I have two students from Turkish German families called Melissa.

With East European immigrants, mostly ethnic Germans whose ancestors emigrated to Eastern Europe centuries ago, the patterns are a bit different. Polish Germans often stick to Polish names and name their kids Lukasz or Bartosz, though sometimes the kids will subsequently germanize their names. One example is the football player Lukas Podolski, who is the son of Polish immigrants and lost the extra z somewhere along the way. Russian Germans tend to go for very old-fashioned German names for children born in Germany, while those still born in Russia have Russian names, which gets you Olympic athletes named Dimitri or Vladimir or Oksana. If you meet a ten-year-old called Waldemar or Adelina, that’s a pretty much a dead giveaway that the parents are Russian Germans. Romanian Germans go for very traditional German names as well and sometimes combine them with Romanian names. For example, I had a student stuck with the unfortunate combination of Tiberius Heinrich who was from a Romanian German family. For some reason, about ninety percent of Romanian Germans have the same two surnames and are called either Müller or Wagner.

Sorry. Comments are closed on this entry.