So, I said I was going to get around to reviewing this, which I’ve had for a couple of months now.

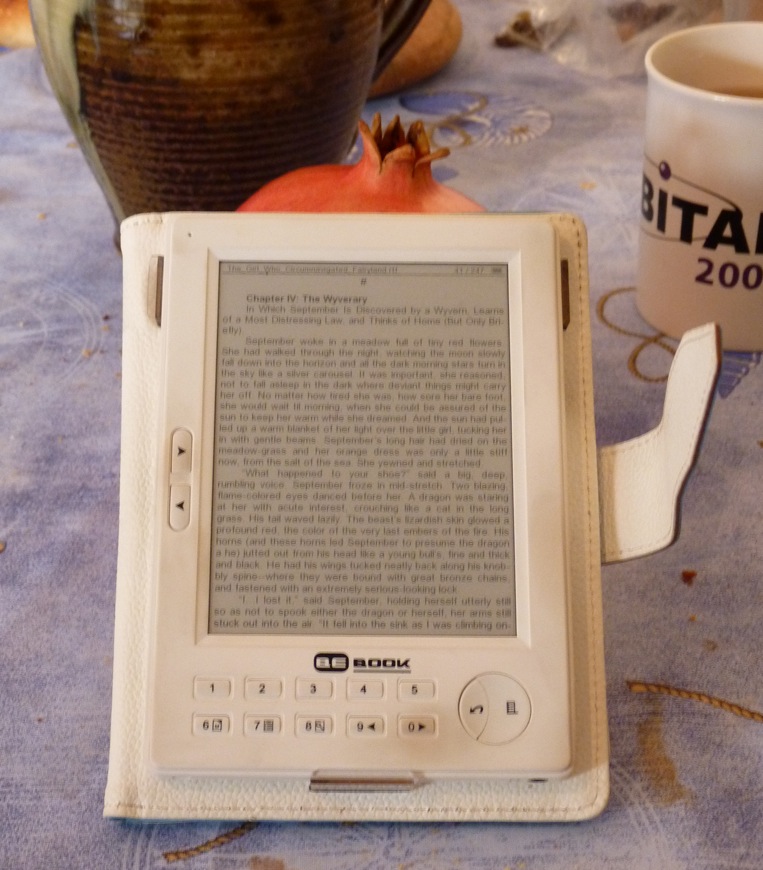

Meet my Bebook Mini:

Just in case you’re wondering about scale, here’s the pomegranate that’s propping it up compared with other, more familiar objects (the pomegranate in question is one from Chili, weighs close to one kilo and has got to be the biggest one I ever saw. It was very tasty, too). The smudges is me reading in quick succession a bad quality newspaper and an ebook–the ink stays on my fingers, and transfers…

I bought this after much hesitation and browsing over at mobileread.com. My initial specifications for an e-reader went something like this:

- Must have e-ink (way better for my eyesight, battery holds out longer), and no glare

- Must support variety of formats (so I didn’t have to worry too much about conversion, and above all didn’t end up stuck with a proprietary format at a time the industry’s still trying to agree on a standard)

- Must have memory card (handy for swapping books, even though it would take a lot of books to fill even 512MB)

- Must be cheap (I wasn’t willing to pay above 250 euros for it).

- Must be relatively straightforward to order (because I wasn’t willing to jump through hoops for this)

I didn’t care so much about wifi (I was going to load books before, say, leaving on a trip), or about touchscreen or other niceties like that. Its primary function would be to read books, not to be another laptop.

This set of criteria turned out to be more restrictive than I thought… In particular, it ruled out both Sony readers (the PRS-300 doesn’t take a memory card, and the PRS-600 has a %%% reflective layer over the screen so that it can be touchscreen). The Kindle I didn’t like so much, mostly because I don’t care for being tied to amazon, for all their usefulness; and the Nook wasn’t/isn’t available in Europe (haven’t been following up on that). I could have got a PRS-505, which is the same brand my father bought, but I had handled it and hadn’t been so much a fan of it; plus, by the time I decided I was going to get an ebook-reader, Sony had phased out the PRS-505 and it was near-unfindable in France. That essentially left me with the Bebook and Bebook Mini, both devices sold by the Dutch firm Endless Ideas. The Bebook is the rebranded version of a Chinese handset, the Hanlin V3, and the Bebook mini is the rebranded version of its successor the V5. The difference between both was screen size: the V3 is 6”, the V5 is 5”. As I’m a fast reader, I was worried I would end up turning way too many pages for the 5” to be viable. But the V3 is older hardware, with fewer graylevels and a slightly older processor, and I didn’t much like the idea of buying old stuff. In the end, I plumped for the Bebook Mini, aka V5.

I’ll gloss over the “straightforward delivery” (it would have been fast, if some unforeseen problems hadn’t held up the package for a few days), and skip to the device itself.

First things first, I’m not regretting the size at all. There’s practically no strain from turning pages, and the big advantage of a 5” over a 6” is that I can fit it into my handbag. That way, I always have something to read.

Second, the battery life on that thing is amazing. I’m using it for more than two hours a day, and I’ve charged it maybe a handful of times since acquiring it. The charge is good for weeks at a time.

What else? Well, it supports a lot of formats, but it’s really unequal: the display options vary greatly between formats. For instance, .DOC support is really lousy, with very few fonts and very few font sizes; RTF is the best I’ve found so far (I’m told f2b is even nicer), with a choice of two fonts, several sizes and some other nice stuff. PDF is OK but not great, since PDF is so heavily geared towards one page size and the screen is much smaller than that (the first ebook I read on the device was Spin in PDF format, and it was a bit of a pain, with huge blanks in the middle of pages). EPUB is the one I’m most used to, since a lot of ebooks are in EPUB format: you can’t change the font, but you have five levels of zoom (though all but the lowest two are actually useless unless you have serious eyesight problems).

On the reader, you can set your books into a folder architecture. You’ll laugh, but some of the other ereaders don’t actually support folders. At any rate, it’s handy to keep stuff organised. There’s an edition of Adobe Digital Editions, too, which I haven’t tested yet (bought the paying books from Baen’s. More on this in a minute). Reading’s pretty nice, with the contrast a little lower than paper–in particular, it means I need decent light to actually make out the words on the page (good thing we’re in summer and I no longer take my bus in the dark). The transition’s a little funky at first (the whole screen goes back, and then flashes into the next page), but you get used to it pretty quickly.

There’s one unexpected bonus: the three different ways to turn the pages. You can hit the rocker on the right-hand side of the reader, hit the two arrow keys at the bottom, or the two on the left-hand side–and all of those will allow you to navigate through the ebook. This hadn’t struck me as practical–at least, not until I got to stand in a packed suburban train, holding onto my handbag with one hand, and turning the pages with the other. The rocker might be the easiest way to turn the pages when I’m sitting, but let me tell you the left-hand buttons are life-savers in a crowd (way easier to hit one-handed).

I really like it, bar one or two things. The first one is that I wouldn’t want to use it for books to keep, as I’m extremely unsure I’d still be able to open those in, say, 20 years (and yes, I’m the kind of person who would like to keep books for 20 years). The second, somewhat related problem with ebooks, is that searching is kind of awkward. You can’t really flip the pages, and if you happen to be looking for a specific passage without wanting to read the whole book in sequence, you’re sort of stuck. Even going to a specific page number is a pain in the neck. (I suppose a search function with a proper keyboard could fix some of that, but I still miss being able to flip through the physical pages. Funny).

And the third, and last problem…

Well, it doesn’t really have to do with the ebook reader, per se. It has to do with ebooks. See, I’d be quite ready to buy them and pay for them–but I’m not allowed to. Many sites on the internet (fictionwise, I’m looking at you) will only sell to visitors from a certain country. The reasoning, I presume, goes something like this: I live in France, so I’m only allowed to buy from French sellers. Who, you wouldn’t know, sell books in French, because that’s what they have the right to sell. Which is great, but I happen to be a little weird linguistically speaking, and I want to read in English (or Spanish. Or whatever). And I know or suspect those US/Canadian sites don’t have the right to sell books in France, but it’s really dumb. The French shops sell the translated French version, and I don’t want that, I want the original, and I just can’t buy it. It’s a little like showing up in a shop with cash, and being told they don’t want to see my kind of people here. Now, all of this made sense at the time we had physical stuff, but in the days of the internet… For ebooks, selling rights by country feels outdated, real fast (not to mention really annoying. I’ve never been so sorely tempted to pirate stuff). Rights by language would be smarter, but I’m sure it’s a lot easier to say than to iron out legally speaking.

Whatever the case, I sure hope this can be sorted out in a smart way (ie, not the way they sorted out the DVDs, which leaves me unable to get English subtitles for Japanese anime unless I buy the UK version. Because everybody in France only wants French subtitles, right? *grr*).

Rant aside (and this isn’t a problem with the device, more with the lay of the land at the moment), this is a terrific little machine. Does what it says on the can, and I’m not regretting the purchase. I just don’t think I’m going to use it for books I’m going to be rereading heavily in the next few years. I’ll get the paper version for those.

Afterword: so where am I getting my books? At the moment, I’m buying from Baen’s webscriptions, one of the few places that sells DRM-free and worldwide. I’m also told that Waterstone’s sells DRM-ed books to any country, but I haven’t tried yet. I’m also downloading a lot of stuff from gutenberg, for free, and from magazines like Tor.com, which has EPUB versions of all their short stories. And I read a lot of the freebies I got from various sources (Hugo voter’s package, Nebula Awards shortlist through SFWA, …).