Books books books

From the book log (crossposted to amazon and goodreads, because reviews are important to authors and I reckon I should start making an effort to review consistently):

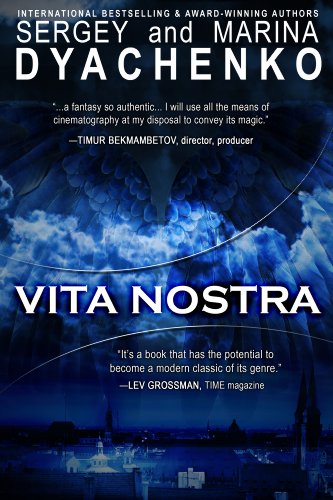

–The Scar, Sergey and Marina Dyachenko: I came to this cold, more or less (it came heavily recommended by a couple of friends, and I’d enjoyed Sergey and Marina Dyachenko’s fantastic Vita Nostra”, but I had no idea what to expect).

This is the story of Ergert Soll, a braggart and bully who goes one step too far and accidentally kills Dinar, the fiancé of student Toria. Egert finds himself cursed by the Wanderer to be a coward–so swamped by fear he’s totally unable to function. Meanwhile, Toria struggles with the loss of her fiancé; and with the appearance in Egert in her life when the latter comes to the city where her father is the Dean of the University. But all is not well: in the background, fanatics known as the Order of Lash seek to bring about the end of the world; and are ready to do anything for this..

This is a tight, character-driven study of two people and how they cope with loss and fear and the rising madness brought by the Order of Lash. I loved the intimate scenes at the university and how they opened up on a larger world, while remaining intimately focused on Toria/Egert. The theme of redemption is one I’m personally always happy to read, and here I thought it was well done if not 100% surprising (but the catharsis at the climax is wonderful done and had me on the edge of my seat). I expected this to be larger-scale and to deal with the brotherhood of Lash; but I’m really it didn’t–part of why it works is the tight focus, and Egert and Toria both having to make stands. I wish we’d seen more from Toria at the climax; the narrative ends up feeling a little unbalanced. But it’s well worth a read, and it’s quite unlike anything else I’ve ever read. Recommended.

–Uprooted, Naomi Novik: Agnieszka lives on the edge of the Wood, a dark and angry power that always seeks to expand, and twists and corrupts everything it touches. Her village (and others) survive because they are protected but the Dragon, a long-lived wizard who has dedicated his life to fighting the Wood. Every ten years the Dragon chooses a girl to serve him; and the girls he picks come back fey, unwilling to settle down in their home villages again. Agnieszka has always thought that her best friend Kasia would be the chosen girl, the one picked by the Dragon to serve him; but she hasn’t counted with her innate talent for magic…

I loved this–easily and effortlessly my favorite read of 2015. I gobbled it up in a day and found myself rereading choice passages. I love the budding relationship between Agnieszka and the Dragon, but also the fact that her friendship with Kasia remains the anchor of the story–and the Wood is such a creepy creation, the stuff of nightmares! I was only 99% sold on the ending (trying not to be spoilery there–I get the idea and love it, but wasn’t quite convinced that Agnieszka could turn aside centuries of hatred). But that doesn’t deter much from the fantastic-ness of this book. Awesome